Re:code L.A. is holding a forum in Northridge Wednesday evening from 6:00 pm to 9:00pm to talk with the community about the city’s $5 million, five-year effort to update its outdated zoning code.

I know. That announcement did not set you on fire. Believe me, I get it.

But you should still think about attending the forum or at least perusing the re:code website.

Here’s why. The zoning code was last fully updated (if that is even the right word) in 1946, when the scattered bits of code that had previously guided development were compiled to create a massive, somewhat unwieldy, and largely insufficient code for a growing suburban-style city.

As you might imagine, 1946 was a very different time in Los Angeles.

Anyone familiar with the history of planning and development in L.A. in the early part of the 20th century knows that policy tools were used both to enforce segregation (see also, here) and, as Occidental College professor Mark Vallianatos wrote in 2013, to create a more “horizontal” Los Angeles as a way

…to avoid some of the perceived ills of dense European and east coast metropolises. Policy makers, planners, voters, industry and real estate interests made choices around land use and infrastructure that enshrined the single family house, the commuter streetcar, and later, the automobile as the building blocks of L.A. Just as London, Manchester, and New York symbolized the scale and challenges of the 19th century industrial city, Los Angeles, with its sprawl and unprecedented car culture, was the “shock city” of the 20th century, a new way of organizing urban land.

Instead of remedying that orientation, since 1946, planners have been adding to the code in such a piecemeal way that the language and codes governing what can or cannot happen on a single property can be both confusing and contradictory.

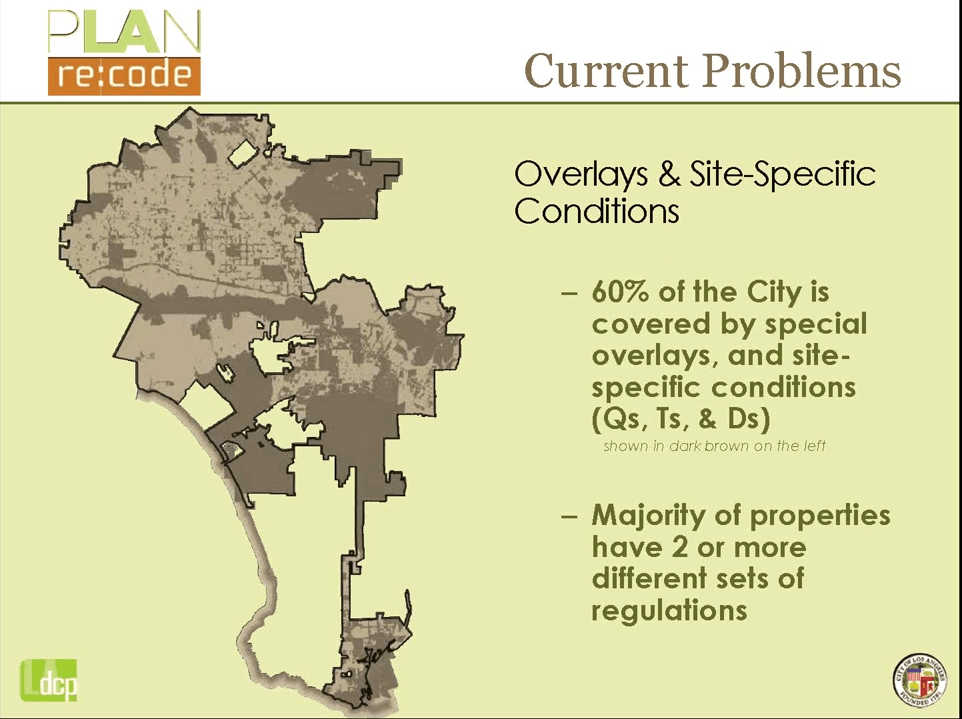

The situation has gotten so bad that as much as 60% of the city is governed by special overlays and site-specific designations (qualified, tentative, and restricted uses). Meaning, according to re:code Project Manager and senior planner, Tom Rothmann, that 61% of city planning staff are currently dedicated to processing of cases and synthesizing competing regulations in order for development to be able to go through.

60% of city is subject to special overlays and site-specific conditions as well as different and sometimes competing sets of regulations. (The darker brown areas). Source: City Planning

Streamlining the code by creating a more flexible and appropriate web-based set of tools will help free up planning personnel to do more actual planning work. It will also make it easier for the end user to know what they can or can’t do with their property before they attempt to undertake that process.

So, the technical reasons for updating the code are more than justified. As is the decision to prioritize the code that will orient Downtown development toward supporting both job and residential growth as its complex set of neighborhoods and land uses continue to evolve.

But questions of how a modernized code will intersect with realities in the surrounding communities in such a way as to foster growth that is more transit-oriented, inclusive, innovative, affordable, healthy, and celebratory of culture and heritage are harder to answer.

Zoning, Rothmann reiterated, pointing at the enormous binder on his desk that housed the city’s current code, represents the tools used to implement the policies set forth in the General Plan and community plans.

Which means that it can’t really address the more complicated questions I often hear in lower-income communities about how to limit displacement, encourage the creation of more green space, or safeguard the cultural character of a community (not just the architectural look and feel of it) in the face of gentrification.

It does not mean zoning cannot ever play a role in addressing some of those issues. Indeed, density bonuses can sometimes be used to carve out some space for affordable units in new developments. And in specific plans, a mix of zoning and planning tools can help make unique community visions a reality. But, generally speaking, zoning can’t tackle these issues independently of planning.

Community members can benefit from learning about how their community is being categorized, just as planners will benefit from hearing community members’ thoughts on those categorizations.

For one, residents could help broaden the conversation around how single- and multi-family neighborhoods are structured.

Concerns about mansionization in more well-to-do and historic neighborhoods have pushed re:code to prioritize finalizing code for single-family neighborhoods. Meaning that re:code’s current discussion of housing focuses on neighborhood character, historic preservation, parking, streetscapes, walls, privacy, height, etc. (see a housing presentation, here) while also ensuring the code is flexible enough to meet the needs of L.A.’s many single-family neighborhoods.

Re:code presentation slide on single-family zones. Source: City Planning

It is also not unusual to see housing double as informal commercial spaces. Where job opportunities are scarce and services are limited, back patios, garages, or home kitchens can be turned into informal restaurants or prep kitchens (for kids or adults vending food outside the home). Or they might serve as repair shops or sources for clothing or other goods — or a mix of both. It all depends on the neighborhood.

It’s a different approach to live/work than you currently see discussed in planning, but it is a live/work arrangement nonetheless. What do planners need to know about how residents live and work in their homes and their neighborhoods so that regulations can better fit their unique realities? Not necessarily so that a community can be frozen in an informal economy framework for the next however many years (if that were even to be possible). But so that people can hone their entrepreneurial skills and build themselves and their communities up from within without fear of being in violation of code. Or so a man whose mother runs an informal diner in his back yard can avoid having law enforcement show up with guns drawn (again), treating his family as if they had been feeding El Chapo.

The likelihood that that level of flexibility in zoning could ever be worked into a plan is probably quite small, unfortunately. But the more planners know about the kinds of activities people engage in, the easier it will be to build a more inclusive set of tools for them to choose from.

And since planners are currently working to categorize land uses that particular kinds of structures might be able to accommodate as part of the new code formula (below), now would seem to be a good time to speak up about the activities you want to see in your neighborhood.

Re:code presentation slide of the proposed zoning code which would classify a property by context (character), form (the structure), frontage (how it engages the street), and the uses (activities) it housed. Source: City Planning

Another aspect of zoning that might be of concern for lower-income communities is what city planners are calling “tienditas.” These are corner markets that have been grandfathered in to neighborhoods that are otherwise zoned as residential.

For people who don’t have easy access to grocery stores or whose funds are so limited that they tend to buy cheap food or staples (e.g. milk) in small quantities, corner markets can be a lifeline. For kids on their way to or from school, they can be a source of breakfast or an after-school snack. Depending on the neighborhood and how local the clerks are, they can serve as a source of community news, since everyone passes through them at some point. And they can also, unfortunately, be a significant nuisance, as sales of liquor and junk food tend to be what keep them afloat.

What would you like to see changed about them? What standards should they meet in order to be permitted to operate? Should the city be working with shop owners to help them offer a healthier selection of products? Should they be zoned out of existence altogether? Or replaced with a more community-enhancing use when the market owner decides to close up shop? Given the multiple roles they play, it is important for planners to know if these shops count as assets for your community.

Some of the above questions are more planning-oriented than zoning-related, but knowing the extent to which small markets contribute to making a residential area better (or worse) is important to both planning and zoning staff as they think about the future composition of a neighborhood.

Re:code presentation slide on downtown-specific development. Source: City Planning

There are a host of other perfectly sound reasons to attend the re:code forum Wednesday, of course.

If you’re a resident of one of those communities, and you’re still not convinced zoning is your bag, it’s OK. I get it. It’s pretty technical and not terribly exciting, and it is genuinely hard to visualize what zoning changes might actually mean for your neighborhood 20 years down the road. (Kudos, by the way, to the members of the re:code team that are working very hard to make code easier to visualize — that is no easy task and they’re doing some tremendous work.)

That said, I keep coming back to zoning’s history.

I keep getting hung up on how very effectively it was once used to deny residents of some communities the opportunity to accumulate wealth via home ownership.

And I can see how it helped strip residents of the ability to have some control over development in their communities. And how vulnerable it has left them to displacement.

Zoning, planning, design — these are processes that are slow-moving and that only crystallize over the longer term. But they certainly leave their mark. Which is why community engagement and particularly that of marginalized community members is so important in the early stages. Not so that past ills can be undone — they can’t. But so that future harms might be averted and more inclusive ways forward might be found.

Adapted from this lastreetsblog article.